January 24, 2021

Marching Cubes optimizations in Unity

In my quest of making a marching cubes voxel engine, performance and optimization have always been a key aspect of development. If one was to make a voxel game, they would need to ensure the game was not laggy or stuttering to make the player experience better and smoother.

Here are some of the tips I have collected over time from optimizing the marching cubes algorithm, some of which are only specific to the Unity game engine, but some are more generalizable. Note that these are for the marching cubes algorithm, and voxel engines.

For the baseline tests, this is the code that I will be using:

If some of the code is unclear, you can look at the code in the repository and look for the file to see what it does. If you can’t find it, you can try going back to the commits of around summer 2020, when I had started making these optimizations and browse around there.

All of the following performance tests will be done with these specs:

- OS: Windows 10, 64-bit

- CPU: Intel i5-8520U @ 1.6GHz 8-cores

- RAM: 8gb

- Unity 2019.3.15f1, release mode build to x86_64 with IL2CPP and .NET 4.x

Table of contents

- Job System (29500 ticks saved)

- Cube index calculation (0 ticks saved)

- VoxelCorners vs stackalloc (300 ticks saved)

- GetVertex (1100 ticks saved)

Job System

The first, and probably the most significant optimization is to use Unity’s Job System, which is a way of implementing thread-safe multithreading in Unity.

In order to be able to use the job system, all of the data has to be in structs and be blittable. This means that regular C# arrays are out of the question. Instead, you have to use Unity’s native arrays. If you are using IJobParallelFor instead of IJob, you may also have to do some 1D-to-3D indexing tricks. Here are the functions for converting between them:

public static int XyzToIndex(int x, int y, int z, int width, int height) {

return z * width * height + y * width + x;

}

public static int3 IndexToXyz(int index, int width, int height) {

int3 position = new int3(

index % width,

index / width % height,

index / (width * height)

);

return position;

}Other than that, converting it to use the job system should be quite straightforward. Again, you can take a look at the baseline implementation (or the most latest one if you want) to look how I converted it.

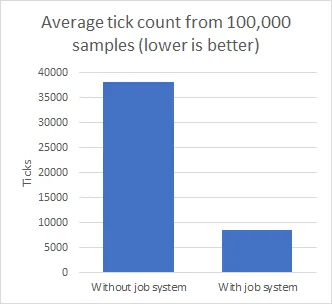

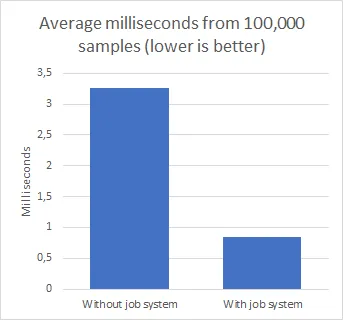

Here are the performance results when comparing using and not using the job system, tested with this code. I ran the marching cubes job on a chunk size of 16^3 voxels 100,000 times, and took the average time of all the runs. The data that was used was generated randomly and generating it was not included in the timing.

When using the job system, the tick count was significantly lower, being around 8500, whereas without the job system it was about 38000. That is a difference of over 4x.

Something I noticed was that when using the job system, the milliseconds were always exactly proportional to the tick count: the milliseconds were exactly 1/10000 of the tick count. I’m not sure why that is.

Calculating the cube index

The cube index is a number ranging [0, 255], which represents the configuration of the densities inside a voxel. To determine the cube index, you need the 8 densities of the voxel, and an isolevel (also known as “isovalue” and “surface level”).

The cube index is easier explained if we look at in binary. Since 255 is the maximum value, the cube index can be represented by an 8-bit integer (=byte). To calculate it, you set each bit of the number to 1 if the density value is less than the isolevel.

The naive way of calculating the cube index looks like this:

public static byte CalculateCubeIndex(VoxelCorners<byte> voxelDensities, byte isolevel) {

byte cubeIndex = 0;

if (voxelDensities.Corner1 < isolevel) { cubeIndex |= 1; }

if (voxelDensities.Corner2 < isolevel) { cubeIndex |= 2; }

if (voxelDensities.Corner3 < isolevel) { cubeIndex |= 4; }

if (voxelDensities.Corner4 < isolevel) { cubeIndex |= 8; }

if (voxelDensities.Corner5 < isolevel) { cubeIndex |= 16; }

if (voxelDensities.Corner6 < isolevel) { cubeIndex |= 32; }

if (voxelDensities.Corner7 < isolevel) { cubeIndex |= 64; }

if (voxelDensities.Corner8 < isolevel) { cubeIndex |= 128; }

return cubeIndex;

}Removing branches from cube index calculation with math.select

As you can see, the naive way introduces a lot of branching. This will be costly on the CPU because of incorrect branch predictions. As we are doing an OR operation inside of each if statement, we can just choose what to OR with by using math.select. Because x|0 is always just x, we can use select to choose between some value and 0, and just do x|value. It would look like this:

public static byte CalculateCubeIndex(VoxelCorners<byte> voxelDensities, byte isolevel) {

byte cubeIndex = (byte)math.select(0, 1, voxelDensities.Corner1 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= (byte)math.select(0, 2, voxelDensities.Corner2 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= (byte)math.select(0, 4, voxelDensities.Corner3 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= (byte)math.select(0, 8, voxelDensities.Corner4 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= (byte)math.select(0, 16, voxelDensities.Corner5 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= (byte)math.select(0, 32, voxelDensities.Corner6 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= (byte)math.select(0, 64, voxelDensities.Corner7 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= (byte)math.select(0, 128, voxelDensities.Corner8 < isolevel);

return cubeIndex;

}Now we have gotten rid of the branches. Let’s simplify it still a bit by removing the casts to byte:

public static byte CalculateCubeIndex(VoxelCorners<byte> voxelDensities, byte isolevel) {

int cubeIndex = math.select(0, 1, voxelDensities.Corner1 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= math.select(0, 2, voxelDensities.Corner2 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= math.select(0, 4, voxelDensities.Corner3 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= math.select(0, 8, voxelDensities.Corner4 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= math.select(0, 16, voxelDensities.Corner5 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= math.select(0, 32, voxelDensities.Corner6 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= math.select(0, 64, voxelDensities.Corner7 < isolevel);

cubeIndex |= math.select(0, 128, voxelDensities.Corner8 < isolevel);

return (byte)cubeIndex;

}Utilizing SIMD code in cube index calculations

It’s looking quite good now, but we can still squeeze it a tiny bit. Because the Burst compiler and Unity.Mathematics work together quite well, we can use math.select with int4 instead of just int. This will generate SIMD code, which means it can operate on more data with only one instruction. There is one more thing you have to do though. In the reference implementation at line 26 you can see that GetVoxelDataUnitCube returns VoxelCorners<byte>. It should be changed to return VoxelCorners<float>. It will cause a little ripple-effect elsewhere in the code. Remember to also convert to isolevel to a float. You can convert between floats and bytes like this (assuming the floats are in range [0, 1]):

float byteAsFloat = myByte / 255f;

byte floatAsByte = (byte)(myFloat * 255);This is how the int4 implementation looks:

public static byte CalculateCubeIndex(VoxelCorners<float> voxelDensities, float isolevel) {

float4 voxelDensitiesPart1 = new float4(voxelDensities.Corner1, voxelDensities.Corner2, voxelDensities.Corner3, voxelDensities.Corner4);

float4 voxelDensitiesPart2 = new float4(voxelDensities.Corner5, voxelDensities.Corner6, voxelDensities.Corner7, voxelDensities.Corner8);

int4 p1 = math.select(0, new int4(1, 2, 4, 8), voxelDensitiesPart1 < isolevel);

int4 p2 = math.select(0, new int4(16, 32, 64, 128), voxelDensitiesPart2 < isolevel);

return (byte)(math.csum(p1) | math.csum(p2));

}If you are using the Burst compiler, it will know how to convert that to SIMD.

When doing the performance test with the first and last iterations of the cube index implementations, I didn’t notice much difference in performance between the tests. The assembly code however, was much cleaner and simpler in the last iteration where Burst generated SIMD code. I would imagine that on some computers the SIMD version is faster, while on some computers there is not much difference like in my case.

The tests from this point forward will be using the SIMD version of the cube index calculation.

VoxelCorners vs stackalloc

If you don’t know what a VoxelCorners<T> is, you can read my other blog post that explains them. In simple words, it is a struct that has 8 fields of type T, and it acts like an array.

If you want to use stackalloc, it’s scope is quite limited; it is limited to the stack, as it name implies. This means that for example the function GetVoxelDataUnitCube would have to be inlined into Execute.

Using stackalloc actually improved it more than I thought. From a sample of 100,000 runs which were done 5 times (5*100000 runs), these were the results:

The original (With VoxelCorners), as I previously showed, was around 8500 ticks. With stackalloc however, it dropped down to around 8100 ticks. If you want, you can also remove the TryGetVoxelData and just use GetVoxelData to remove one branch and bypass the bounds checks. This further reduced the ticks from 8100 to around 7800.

This however complicated the code a bit by removing the GetVoxelDataUnitCube function and inlining it. I guess you could get around that by passing the float* from the stackalloc into GetVoxelDataUnitCube and populating it there.

GetVertex instead of VertexList

Inside of GenerateVertexList and after the if statement is the code that calculates to position of a single vertex. We can isolate that into a function, and call that function when we need a new vertex. This will allow us to get rid of VertexList. The function looks like this:

public static unsafe float3 GetVertex(int index, float* voxelDensities, int3 voxelLocalPosition, float isolevel) {

int edgeStartIndex = MarchingCubesLookupTables.EdgeIndexTable[2 * index + 0];

int edgeEndIndex = MarchingCubesLookupTables.EdgeIndexTable[2 * index + 1];

int3 corner1 = voxelLocalPosition + LookupTables.CubeCorners[edgeStartIndex];

int3 corner2 = voxelLocalPosition + LookupTables.CubeCorners[edgeEndIndex];

float density1 = voxelDensities[edgeStartIndex];

float density2 = voxelDensities[edgeEndIndex];

return VertexInterpolate(corner1, corner2, density1, density2, isolevel);

}Then in the marching cubes job file you can use that function like this:

float3 vertex1 = MarchingCubesFunctions.GetVertex(MarchingCubesLookupTables.TriangleTable[rowIndex + i + 0], densities, voxelLocalPosition, isolevel / 255f);

float3 vertex2 = MarchingCubesFunctions.GetVertex(MarchingCubesLookupTables.TriangleTable[rowIndex + i + 1], densities, voxelLocalPosition, isolevel / 255f);

float3 vertex3 = MarchingCubesFunctions.GetVertex(MarchingCubesLookupTables.TriangleTable[rowIndex + i + 2], densities, voxelLocalPosition, isolevel / 255f);Now we can remove the GenerateVertexList function, and as a result of that, also the edge table from MarchingCubesLookupTables. This will have to generate some vertices multiple times, but at least there are no expensive allocations coming from VertexList. It also removed a bit of branching and a for loop.

Converting from VertexLists to the GetVertex function dropped the average ticks from 7800 to around 6700, improving it by 1100 ticks.